This article discusses the details of genocide and explores horrific acts historically and currently committed against individuals of distinct racial, religious, national and ethnic groups – this article includes images to emphasise these horrific acts.

The darkest depths of human history often involve mass violence, war, torture, and unspeakable atrocities. Genocide is an offence which exists on its own, superior level of evil. Genocide is defined by the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide as:

“any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Genocide found its roots, unsurprisingly, in the atrocities committed in Nazi Germany resulting in its ‘Final Solution to the Jewish Question’, known across the world as The Holocaust. During this period, Raphael Lemkin, the voice of the need for a crime of genocide, coined a crime of barbarity, which he defined as:

“Whosoever, out of hatred towards a racial, religious or social collectivity, or with a view to the extermination thereof, undertakes a punishable action against the life, bodily integrity, liberty, dignity or economic existence of a person belonging to such collectivity”

This definition eventually found its way into the Nuremberg Trials when describing the offences committed by the leaders of the Nazi regime. Interestingly, none of these individuals ever faced offences of genocide, it was not a recognised offence until UN General Assembly Resolution 96 in 1946, and did not become a binding offence until 1948 with the adoption of the Genocide Convention.

In the years that have followed, including the present day, international tribunals and legal systems have struggled to truly contemplate and understand genocide, however, numerous NGOs and groups now recognise that genocides happen, broadly, in 10 distinct (though not necessarily consecutive) stages. In this piece, we will explore the 10 stages of genocide along with examples of where these have been committed, and where they currently are.

Stage 1 – Classification

The initial stage in a genocide is for the party subject to the genocide to be identified and classified. This is most notably applied through a ‘them and us’ attitude segregated by race, religion, nationality or ethnicity. In Nazi Germany this was ‘German and Jew’, in Rwanda this was ‘Hutu and Tutsi.’ As stated by Genocide Watch:

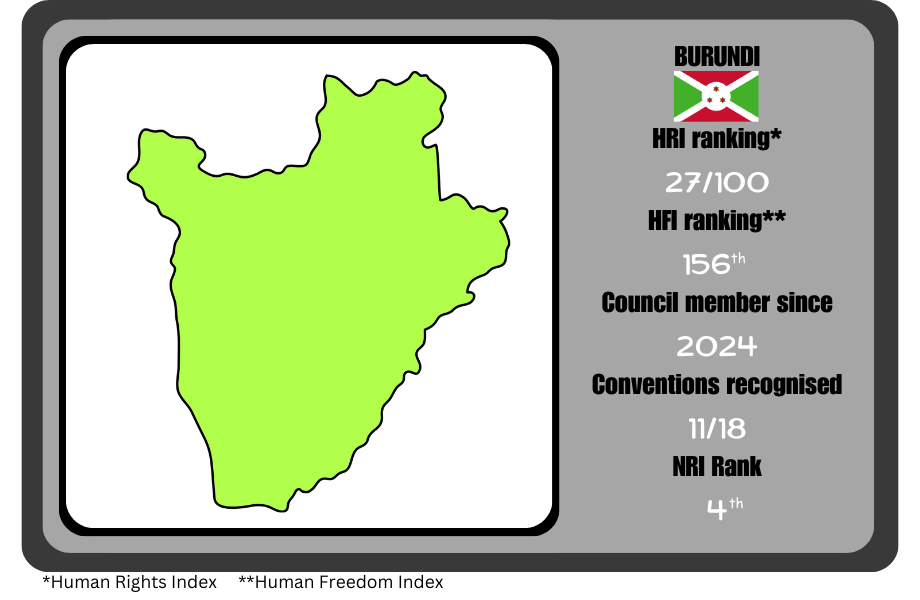

“Bipolar societies that lack mixed categories, such as Rwanda and Burundi, are the most likely to have genocide. One of the most important classifications in the current nation-state system is citizenship in a nationality. Removal or denial of a group’s citizenship is a legal way to deny the group’s civil and human rights.”

The 1933 Denaturalisation Act was used to enable the Nazi Government to systematically strip Jews of their German citizenship before the 1935 Reich Citizenship Act which created further division by implementing a tiered hierarchy of citizenships.

Stage 2 – Symbolisation

The classification of individuals is furthered by symbolising these individuals, distinguishing them in some way from the ‘others’. Whilst classification and symbolism are an inherently human thing to do, something which occurs every single day, it is the intent and hatred behind the symbolisation which leads to genocide.

The yellow star is one of the most recognisable symbols used in a genocide. Other symbols used include the blue scarf for Eastern Cambodians. Symbols don’t always have to be ones to designate the ‘undesirable’ group, there are often parallel symbols which designate the group committing the genocide. In Nazi Germany, the most notable symbol was the Swastika. Other symbols included the Totenkopf, the skull which adorned many SS uniforms.

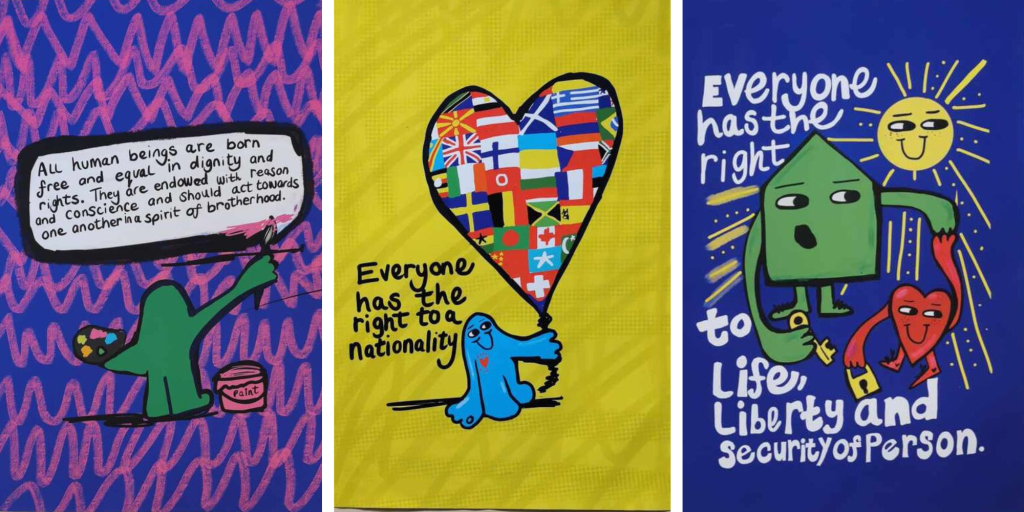

Stage 3 – Discrimination

It is with this third stage where ‘formal’ action is taken. The dominant group will employ the political and legal system in order to remove the rights of the other group. Rights that are often targeted include human and civil rights, the right to vote and participate in elections, and the right to citizenship. These laws and actions seek to empower the dominant group and legitimise their cause.

Genocide Watch have designated the UK Government as being actively involved in Stage 3 against refugees and members of the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller community. The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 criminalises certain aspects of GRT life and leads to further discrimination and the plans to ‘offshore’ asylum seekers in Rwanda is continuing despite being held unlawful.

Stage 4 – Dehumanisation

Whilst a distinct stage itself, dehumanisation is something which occurs throughout a genocide. By reducing a group to a symbol or denying them rights, they are more easily able to be seen as sub-human and as deserving less than the dominant group. Dehumanisation is a psychological state whereby it is easier to harm and disregard the thoughts and feelings of others, considering a people as somehow inferior makes it easier to justify extreme acts against them.

The Holocaust Memorial Day Trust notes that:

“Those perceived as ‘different’ are treated with no form of human rights or personal dignity. During the Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, Tutsis were referred to as ‘cockroaches’; the Nazis referred to Jews as ‘vermin’.”

Stage 5 – Organisation

Genocide cannot be committed by accident, there is always a form of organisation to it. Though, the degree of organisation can vary, some genocides, such as the Nazi regime, are highly organised at a supranational scale and spanning multiple territories. Other genocides, often perpetuated by terrorist groups, are decentralised.

The need for organisation makes inter-state conflicts, such as civil wars, prime breeding ground for genocides to occur. States receive an influx of arms and military support and civilian populations are placed into a much more vulnerable position.

Often, the state will provide specific training in aid of a genocide. This can include the development of guerilla militias, secret police, or entire political divisions.

Stage 6 – Polarisation

Polarisation takes Stage 3 to the extreme level. Again, laws are used and employed to further separate the groups, not only removing more rights of the marginalised groups, but criminalising those within the majority group from supporting or engaging with the minority are common.

It is often at this stage where the majority group becomes more extreme and begins to target those outliers within the group, as Genocide Watch have stated:

“Extremist terrorism targets moderates, intimidating and silencing the center. Moderates from the perpetrators’ own group are most able to stop genocide, so are the first to be arrested and killed. The dominant group passes emergency laws or decrees that grants them total power over the targeted group.”

Anybody who remains silently supportive of the minority are now too fearful to speak out and the majority group have ultimate power and control. Genocide Watch considers South Africa to be at Stage 6, noting:

“Millions of immigrants from poorer African countries have settled in South Africa since 1994. Xenophobia against them has resulted in violent attacks, notably in 2008 and 2015, when over 50,000 immigrants were displaced. Due to anger about unemployment, high crime rates, and poor public services, young South Africans blame immigrants for taking jobs away from them. No perpetrators of the 2008 attacks on foreigners, the 2015 Durban riots, or the 2019 violence in eThekwini have been brought to justice. The same impunity results from non-prosecution of murders of white farmers. The Marxist, racist Economic Freedom Front party of Julius Malema encourages these murders, which are meant to terrorize farmers into emigrating from South Africa.”

Stage 7 – Preparation

Euphemisms such as ‘ethnic cleansing,’ ‘purification,’ or ‘counter-terrorism’ are used to prepare for the active stage of genocide. Mass development of genocidal aides take place, concentration camps are built, groups are trained to displace and move groups, and the rhetoric against the minority group is severely ramped up.

Groups will often disguise a genocide as self-defence, warning citizens and members of the majority that if the minority group is not destroyed then the majority group will be instead. The ability to prevent the genocide at this stage is incredibly difficult, with actions such as prosecution and elections actually being able to trigger the active genocide, rather than prevent it.

The Rwandan genocide was committed under the guise of self-defence, with Human Rights Watch reporting:

“In October 1990, two weeks after the first RPF attack and when the invaders were already retreating, local officials and political leaders incited Hutu living in Kibilira commune to kill some three hundred Tutsi neighbors in a “self-defense” operation. The officials spread rumors that RPF combatants had killed Hutu in nearby areas and were about to attack the Hutu of Kibilira commune. This massacre, like fifteen other attacks launched by Hutu against Tutsi before April 1994, was far from the battlefront and the Hutu faced no imminent danger from RPF combatants, far less from the neighbors they attacked.”

Stage 8 – Persecution

This is the first stage where the Genocide Convention may formally recognise a genocide.

The minority group is targeted and systematically oppressed. Victims are separated from the wider community, often though forced relocation, segregation, or confinement in camps. The persecution is fueled by propaganda, contributing to a hostile environment where acts of violence against the minority group are normalised and encouraged.

The right to a trial is either removed entirely or special tribunals are created by the majority group. Specific death lists may be drawn up and notable individuals targeted. During World War 2, the Nazis established numerous ghettos where Jews were isolated, resulting in uncountable deaths from disease, starvations, killing or deportation.

The Uyghur Muslims in China are currently being persecuted, with the US Holocaust Memorial Museum noting that:

“China has created a large system of arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance. Approximately one million Uyghurs are currently imprisoned in detention centers, for reasons as simple as practicing their religion, having international contacts or communications, or attending a western university. The Chinese government has defended the camps as “vocational training centers” aimed at combating violent extremism. Leaked government documents reveal that the state is in fact targeting people based on religious observance, such as praying or growing a beard, as well as family background.”

Stage 9 – Extermination

Once an active extermination has begun, the only way to prevent it is an overwhelming armed intervention. Escape corridors and safe zones need to be established with heavily armed international protection.

Most genocides will never truly succeed, the minority group are almost never fully destroyed. However, the group will forever be altered and impacted by the genocide. In most modern cases, mass rape is a normal characteristic of genocides and is used to destroy the victim group. Similar modern means include forced sterilisation and abortion.

Mali is one of the countries currently engaged in an active genocide, despite the presence of UN Peacekeeping forces, ethnic groups including the Fulani, Dogon, and Tuareg are actively being targeted and killed by militias stemming from the 2011 Libyan Civil war and 2012 Mali coup d’état.

In the most organised and wide scale extermination to date, the Nazis built and utilised six large-scale death camps, the most notable being Auschwitz-Birkenau, at which just under 1 million Jews were murdered in gas chambers.

Stage 10 – Denial

Denial is less a distinct stage and more a continuing state. The majority group, even many years after the genocide, and often once that group is no longer a majority, will deny the atrocities as a genocide and continue to engage in defensive arguments in support of the horrific acts committed.

Genocide Watch have noted that:

“During and after genocide, lawyers, diplomats, and others who oppose forceful action often deny that these crimes meet the definition of genocide. They call them euphemisms like “ethnic cleansing” instead. They question whether intent to destroy a group can be proven, ignoring thousands of murders. They overlook deliberate imposition of conditions that destroy part of a group. They claim that only courts can determine whether there has been genocide, demanding “proof beyond a reasonable doubt”, when prevention only requires action based on compelling evidence.”

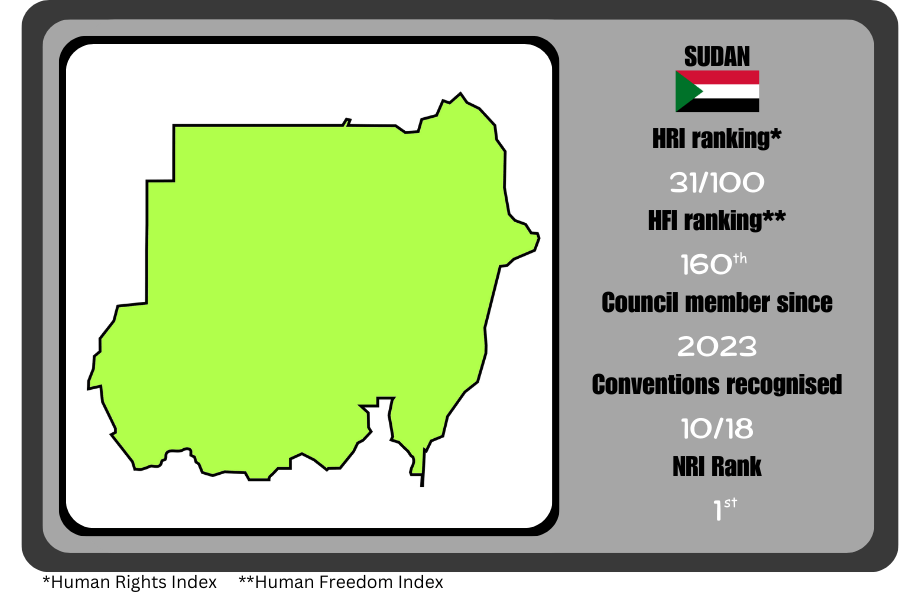

Denial can include mass cover ups of atrocities, the destruction of documents, bodies burned, witnesses murdered, and investigations hampered. Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir, the former President of Sudan, and only individual currently being investigated by the International Criminal Court for Genocide, is currently being harboured in Sudan despite an international arrest warrant being issued.

What we see repeatedly when genocides are actively being committed is a lack of action by states and instead to focus the debate on the intricate details such as the definition of genocide. This takes away from the real issue that is the lives of millions of individuals currently being subjected to atrocities. As Philippe Sands has asked:

“The real question is, why does it matter if we call it a genocide?”

Avaia Williams – Founder

This blog was published on 25 October 2023