Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), protects an individual’s right to life. Article 2 states that:

“Everyone’s right to life shall be protected by law. No one

shall be deprived of his life intentionally save in the execution of

a sentence of a court following his conviction of a crime for which

this penalty is provided by law.

Deprivation of life shall not be regarded as inflicted in

contravention of this Article when it results from the use of force

which is no more than absolutely necessary:

(a) in defence of any person from unlawful violence;

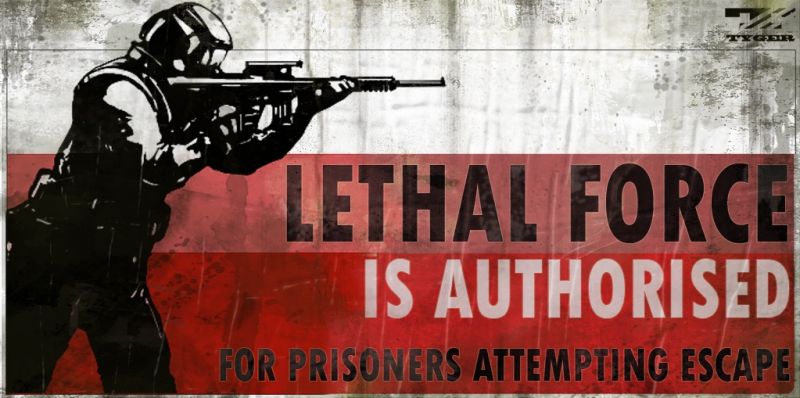

(b) in order to effect a lawful arrest or to prevent the escape

of a person lawfully detained;

(c) in action lawfully taken for the purpose of quelling a riot

or insurrection.”

Protocol 6 to the ECHR removed the death penalty as a form of judicial punishment, whilst protocol 13 to the ECHR removed the death penalty during war time. In effect, it is now against a person’s Article 2 rights to sentence them to death regardless of crime or circumstance.

Contrary to popular belief, there is no law that allows a person to be sentenced to death for the crime of treason in the UK. This was officially abolished via section 36 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998.

This only removes the death penalty in regard to criminal sentences, there are still circumstances where the state may take the life of a citizen without infringing upon their right to life.

The second part of Article 2 includes exceptions to the right, it states that it shall not be a breach of a person’s Article 2 right if they are killed via a use of force that is reasonable in the circumstances. This is why it is not against the law for armed police officers to shoot and kill people where those suspects have, for example, a firearm or are committing acts of terrorism. This still requires the use of force to be reasonable and requires such use of force to be absolutely necessary.

In the case of McCann v UK [1995], the government ordered special forces soldiers from the SAS to arrest three suspected terrorists, however, during the operation the soldiers shot and killed all three suspects. The spouses of the suspects brought a case against the United Kingdom arguing that it was an unreasonable use of force to shoot the suspects and that it was not absolutely necessary.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) ruled that the soldier’s actions of shooting the suspects was NOT in breach of Article 2, however, the ECtHR did rule that the United Kingdom Government WAS in breach of Article 2. The Court stated at paragraphs 213-214 that:

“having regard to the decision not to prevent the suspects from travelling into Gibraltar, to the failure of the authorities to make sufficient allowances for the possibility that their intelligence assessments might, in some respects at least, be erroneous and to the automatic recourse to lethal force when the soldiers opened fire, the Court is not persuaded that the killing of the three terrorists constituted the use of force which was no more than absolutely necessary in defence of persons from unlawful violence within the meaning of Article 2.

Accordingly, the Court finds that there has been a breach of Article 2 of the Convention.”

Article 2 also contains a procedural element; it requires the state to investigate where lethal force has been used. In most cases this is carried out by the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) formerly called the IPCC. In some cases, an inquest may be ordered if there is doubt regarding how the suspect died.

In the case of Jordan v UK (2003), the police shot and killed a suspect. Witnesses to the shooting stated that the suspect was shot without warning, that he was unarmed and that he was passive at the time of the shooting. An inquest was ordered, however, there were substantial problems regarding evidence and there were significant delays. The family of the suspect appealed to the ECtHR who found that, due to multiple failures in the way the inquest had been conducted, the government had failed to comply with the procedural element of Article 2 and that there had thus been a violation.

The courts have been extremely reluctant to imposes a ‘positive duty’ on the state regarding Article 2, that being a duty for the state to actively prevent the deaths of its citizens. Where there is a real and immediate risk to a citizen’s life then the state may be held to have a duty to safeguard that person’s life.

In the case of Osman v UK (2000), the applicant brought a case to the ECtHR after the police failed to prevent a murder despite numerous complaints being made to them regarding the defendant’s behaviour towards the victim. Osman argued that the death of the victim was a breach of Article 2 as the state did not prevent it. The Court ruled that there was no breach to Article 2 as the police acted reasonably with the evidence they were presented with, there was no reason to suspect that the defendant would kill the victim.

In the case of Kilic v Turkey (2005), unlike in Osman, the Court did find a breach of Article 2 as the state had failed to carry out a proper investigation where the facts and evidence showed there was a real and immediate risk to the victim’s life.

In short, Article 2 prohibits the use of death as a criminal penalty and also requires the state to actively investigate deaths where they occur due to ‘agents of the state’. There is, however, no obligation on the state to actively protect the lives of all citizens in most circumstances.

This article was published on Saturday 18th July 2020

Should you have any questions, comments or concerns about this article then please do not hesitate to contact us