Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), protects an individual’s right to not be subject to torture, inhuman or degrading treatment by a state or an agent of the state. It is the shortest Article in the entire convention. Article 3 states that:

“No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

In principle, Article 3 is the only ‘absolute right’ afforded under the ECHR, this means that it is the only right that the state can, under no circumstance, ever breach regardless of any factors that may be present. The significance of this right can be seen in the fact that it is protected in several other international treaties such as the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and the United Nations Convention against Torture.

Article 3 is only usually relevant in cases where a person is under the control of the state, that is, the person is detained or restricted by the state in some way. Most cases concerning Article 3 therefore come from three main sources

- Individuals serving a sentence inside of a prison or immigration detention facility;

- Individuals detained in custody by the police or other similar agents of the state (whether this be detained in a police station, police vehicle or simply the element of detention is present); and

- Individuals detained inside of a mental health setting such as a psychiatric hospital.

There are technically many things which could breach Article 3, however, due to the severity of Article 3 breached and due to the absolute nature of Article 3, the Courts have imposed a severity threshold, that is a minimum level of suffering that must be present in order to trigger Article 3.

In the case of Pretty v UK (2002), a woman suffering with motor neuron disease wished to have her husband assist her in taking her life, a crime under UK law. Pretty asked the government for a guarantee that they would not prosecute her husband, however, this was refused. Pretty took the case to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) arguing that the UK Government was breaching her Article 3 rights as she was suffering from the disease. The Court held no violation of Article 3 and stated at paragraph [52] that the minimum level of severity:

“involves actual bodily injury or intense physical or mental suffering. Where treatment humiliates or debases an individual showing a lack of respect for, or diminishing, his or her human dignity or arouses feelings of fear, anguish or inferiority.”

In Pretty, the state had no involvement in causing or affecting the disease, it was something outside of their control and therefore Article 3 was not able to be triggered. There often needs to be some positive step on behalf of the state in order for Article 3 to be relevant.

Article 3 is split into ‘Torture’ and ‘Inhuman and degrading treatment’, ergo, a person may be treated in a way that is not considered torture but would be considered inhuman, or, treatment may be considered to breach all three elements. What triggers each element of Article 3 is extremely subjected and depends on the specific facts of each case. In practice there are several elements which may be particularly relevant in assessing a breach of Article 3 such as:

- The amount of time that a person is subject to a particular thing;

- Purposeful acts done by the state or its agents;

- The degree of harm suffered by the person subjected to treatment;

- The age, sex and health of the person subjected to treatment.

Article 3 triggers – Torture

Torture is the most severe form of treatment under Article 3 and therefore treatment must reach a significant degree of severity in order to be considered as torture.

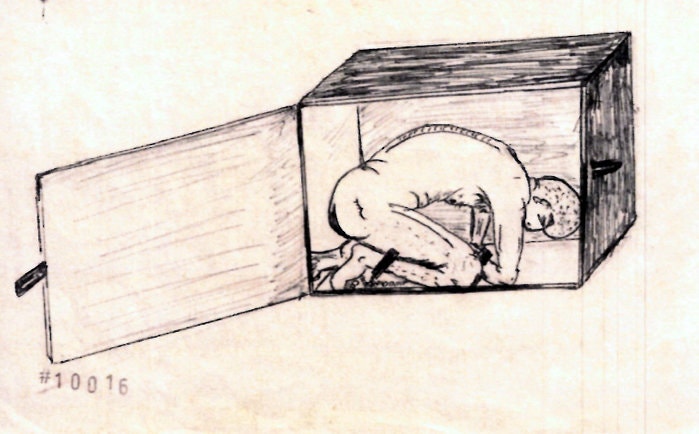

In the case of Ireland v UK (1979-80), multiple suspected IRA terrorists were detained in various locations and subject to interrogation by the police and intelligence officials. The detainees were subjected to what are known as ‘the five techniques’, these interrogation techniques consisted of:

- Forcing the detainees to stand in stress positions for many hours;

- Placing a hood over the detainees heads at almost all times;

- Subjecting the detainees to continuous and loud noise;

- Depriving the detainees of sleep; and

- Depriving the detainees of food and water.

The detainees argued that the government had breached their Article 3 rights by virtue of subjecting them to such treatment. The ECtHR ruled that the treatment was NOT torture as it did not reach the required severity, however, the Court did rule that the treatment was inhuman and degrading. Many academics and lawyers have argued that the Ireland decision was wrongly decided and that such treatment should have been considered torture. In 2018 the Irish government petitioned the ECtHR to revise their earlier judgement, however, the Court refused to revise it (The revision case can be viewed here).

In the case of Nevmerzhitsky v Ukraine (2005), a man who was detained in a mental health facility was force fed after going on a hunger strike. In force feeding the man, the doctors used handcuffs, a mouth widener and a rubber tube. The hospital had failed to provide medical reports or evidence that the force feeding was necessary. The ECtHR ruled that as there was no proof of necessity, that force feeding the patient constituted torture and held that his Article 3 rights had been breached to this high degree.

In the case of Munjaz v Ashworth Hospital [2005], a man was detained in Ashworth high security hospital, during his detention he was secluded on multiple occasions for varying periods of time, in one case for 18 days. Ashworth’s seclusion policies were different to national guidance and the policies at all other psychiatric hospitals, mainly, the Ashworth policy provided for less frequent reviews of a patient’s seclusion. The House of Lords held that seclusion could violate Article 3 if it was used improperly or used as a form of punishment, however, the House ruled that Ashworth had not violated Article 3. Lord Steyn provided a powerful dissenting judgement in the case, at paragraph [48] he stated:

“If Ashworth Hospital is permitted in its discretion to reject the Code, lock, stock, and barrel, regarding seclusion, it will be open to other hospitals to do so too […] the judgment of the majority of the House permits a lowering of the protection offered by the law to mentally disordered patients […] How society treats mentally disordered people detained in high security hospitals is, however, a measure of how far we have come since the dreadful ways in which such persons were treated in earlier times. For my part, the decision today is a set-back for a modern and just mental health law.”

The House of Lords decision in Munjaz was upheld by the ECtHR in Munjaz v UK [2012].

It can be seen from these cases how high the threshold for torture is in practice, in most cases there has to be a serious, purposeful and physical act by the state or its agents towards another person.

Article 3 triggers – Inhuman or degrading treatment

Unlike for torture, the threshold for inhuman or degrading treatment is somewhat significantly lower and is an easier threshold to prove.

In the case of Keenan v UK (2001), a prisoner (MK) expressed suicidal thoughts and plans to prison staff, was misdiagnosed by a prison psychiatrist and was placed in segregation for a significant period of time. Whilst in segregation, prison staff left MK unsupervised for a short period, during this time MK died by suicide. The ECtHR held that the lack of adequate treatment, the lack of monitoring and the imposition of segregation as a punishment all amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment. The case of Keenan is an incredibly important case for protecting the rights of detainees who suffer from mental illness. At paragraph [110] of the judgement the Court stated:

“The lack of appropriate medical treatment may amount to treatment contrary to Article 3. In particular, the assessment of whether the treatment or punishment concerned is incompatible with the standard of Article 3 has, in the case of mentally ill persons, to take into consideration their vulnerability and their inability, in some cases, to complain coherently or at all about how they are being affected by any particular treatment.”

The Court effectively ruled that the state must be extra vigilant and appreciative to the difficulties faced by those who suffer with mental illness.

In the case of Van Der Ven v The Netherlands (2003), a man was detained in a maximum-security prison after being sentenced for murder, GBH and rape. In the prison he was under constant surveillance, subject to routine weekly and other ad hoc strip searches, allowed only monthly visits and provided only 2 phone calls a week. The ECtHR ruled that the routine strip searches were carried out despite there being no concrete security need, they were routine and not based on intelligence, therefore, the Court ruled that these security measures amounted to inhuman or degrading treatment.

In the case of ZH v Metropolitan Police Commissioner [2012], an autistic teenager was restrained and detained by police officers after he fell into a swimming pool due to the negligence of the officers. The teenager had force applied to his body whilst leg restraints and two pairs of handcuffs were placed onto him. He was then transferred into a police van whilst still in the restraints and still soaking wet from the swimming pool, he was unsupervised in the police van. The High Court held that, taking the entire situation into account, there was a clear breach of Article 3 and that the treatment of the teenager was inhuman or degrading.

In short, Article 3 prohibits states from torturing individuals and also prohibits states from subjecting individuals to any treatment that would be considered as inhuman or degrading. Treatment that could fall foul of Article 3 is dependant on the exact nature of the case and the circumstances that surround it.

*Abu Zubaydah has been detained without trial by the United States in Guantanamo Bay for almost 20 years

This article was published on Wednesday 5th August 2020

Should you have any questions, comments or concerns about this article then please do not hesitate to contact us