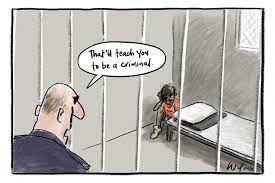

Shocking crimes involving children always draw the public’s attention to one of society’s biggest dilemmas: how should society address cases where children become perpetrators of alarming offenses?

Article 3(1) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) states that:

“in all actions concerning children […] the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.”

The Age of Criminal Responsibility (“ACR”) is therefore a subject that requires careful consideration, as it involves finding a delicate balance between holding young individuals accountable for their actions while also recognising their potential for rehabilitation.

In this blog post, we will explore the concept of the ACR, examine different perspectives and discuss the potential implications and alternatives for dealing with young offenders.

Most countries worldwide, have established a minimum age for criminal responsibility (“MACR”), although a few exceptions exist. Nevertheless, the specific age threshold for MACR varies significantly, ranging from 7-18 years old (in England and Wales, the MACR is 10). The determination of this threshold is usually influenced by cultural, historical and legal factors, as well as a general consideration of child development and their capacity for moral and cognitive judgment.

Lowering the ACR?

Some proponents argue that setting a low ACR is necessary to establish clear boundaries and ensure accountability for criminal acts committed by children. They assert that early intervention can deter further criminal behaviour and provide appropriate support for the victims. Furthermore, it is argued that a low ACR promotes a sense of justice by treating children who commit serious offenses equally to adults.

Raising the ACR?

Conversely, there is a growing movement advocating for raising the ACR. Supporters argue that children, due to their limited cognitive and emotional development, may not fully understand the consequences of their actions. They contend that the focus should be on rehabilitation rather than punishment, aiming to address the root causes of delinquency and provide the necessary guidance and support to reintegrate young offenders into society.

Alternatives to Criminalisation

In response to concerns about criminalising young individuals, alternative approaches have gained attention. One such approach is the implementation of restorative justice practices, which focus on repairing the harm caused by criminal behaviour, fostering empathy and promoting accountability through dialogue and community involvement. Diversion programs, counselling and educational interventions are also gaining recognition as effective ways to address youth offending while emphasising rehabilitation.

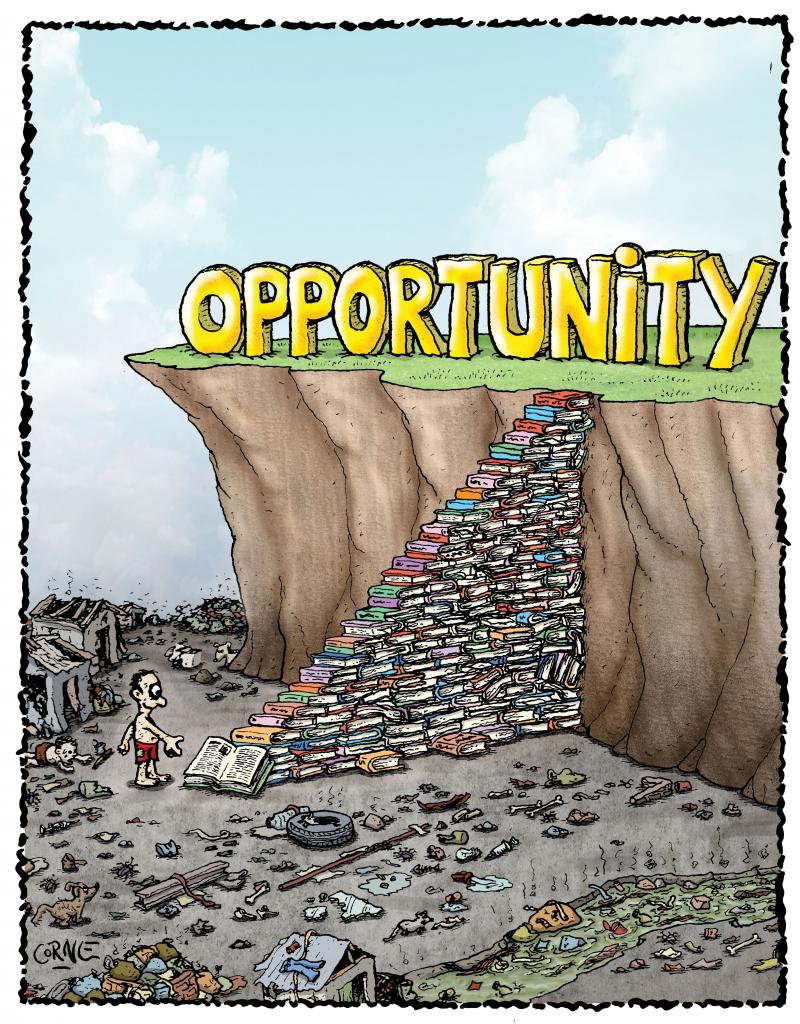

Investing in education and prevention programs can play a crucial role in reducing juvenile delinquency rates. Providing access to quality education, mentorship and extracurricular activities can help steer children away from criminal behaviour and offer them positive alternatives for personal growth.

Conclusion

Determining the ACR is a complex task that necessitates careful consideration of numerous factors. While there are valid arguments for both lowering and raising the age threshold, the focus should remain on finding a balance between accountability and rehabilitation for young offenders.

Ultimately, society must strive to create a fair and just system that addresses the needs of young individuals, promotes their rehabilitation and ensures public safety.

Thekla Sorokkou – Writer

This blog was published on 15 July 2023