Voting is a fundamental democratic right that should be accessible to all eligible citizens, including those detained by virtue of their mental health. However, individuals in mental health services often face significant barriers to exercising this right. Given that this demographic are often subject to some of the most severe interference with human rights, including enforced medication, restraint and seclusion, and significant periods away from all forms of support, it is only right that their voice be empowered to be heard in elections.

Under the Representation of the People Act 2000 (RPA), an individual is entitled to vote if they are registered in the register of electors of a constituency where they are resident. This includes long-term residents in hospitals, who can register to vote from their hospital address if the length of their stay is sufficient to consider them as residents. The RPA amended the MHA to note:

“A person to whom this section applies shall […] be regarded for the purposes of section 4 above as resident at the mental hospital in question if the length of the period which he is likely to spend at the hospital is sufficient for him to be regarded as being resident there for the purposes of electoral registration.”

However, there are significant exceptions to this general rule, particularly concerning offenders detained in mental hospitals under specific sections of the MHA where these detentions concern a forensic nature (such that they are detained in connection with some criminal element). Individuals detained under sections 37 (criminal court hospital order), 38 (interim criminal court hospital orders), 44 (magistrates court hospital order), 45A (higher courts hospital order), or 47 (transfer of prisoner to hospital) of the Mental Health Act 1983, or under section 5(2)(a) of the Criminal Procedure (Insanity) Act 1964 (which requires the courts to make one of the preceding orders in certain cases), are not entitled to vote. These provisions reflect the law in respect of those serving custodial prison sentences, with section 3 of the Representation of the People Act 1983 providing that:

“A convicted person during the time that he is detained in a penal institution in pursuance of his sentence or unlawfully at large when he would otherwise be so detained is legally incapable of voting at any parliamentary or local government election”

Though, the rights of prisoners to vote is something which the UK Government continues to be in breach of international law on, with an effective blanket ban still being in place against the ruling of the European Court of Human Rights in Hirst v UK (No 2) (2006).

Patients who are eligible to vote can register using their hospital address if they have been, or are likely to be resident there, for a sufficient period. They may also choose to register at their home address or another residence by making a “declaration of local connection,” specifying an alternative address within the UK. This flexibility is vital for ensuring that patients can participate in elections regardless of their current living situation, especially given the fact that thousands of mental health placements are outside the local area where the person usually resides.

When it comes to the act of voting, voluntary patients and those detained with appropriate leave can attend polling stations. In contrast, other detained patients may only vote by post or by proxy. This ensures that all patients, regardless of their ability to physically visit a polling station, can still exercise their right to vote.

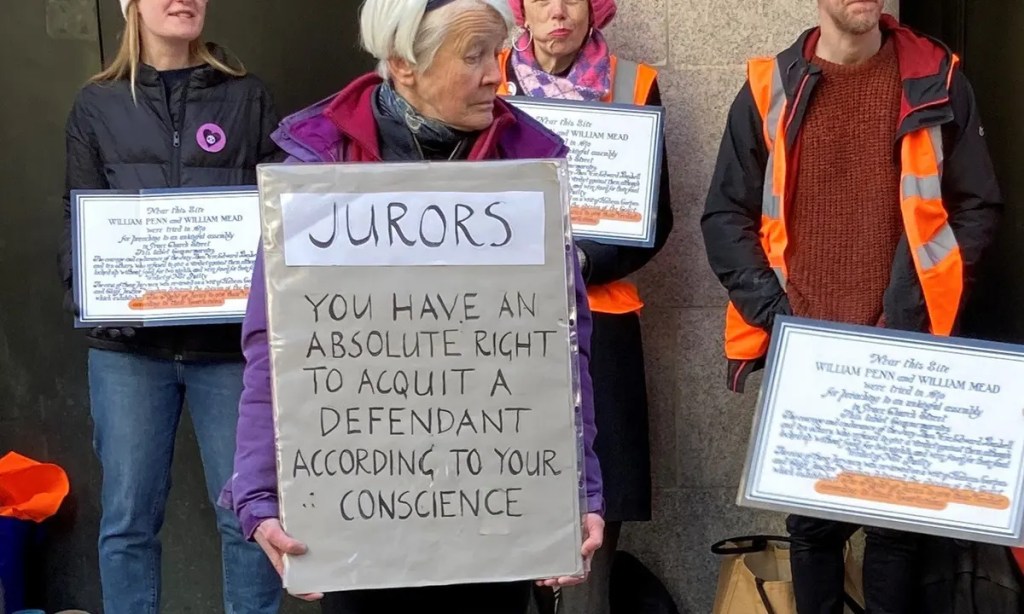

Whilst the black letter of the law states this, the practicalities are not reflective of this position. One of the primary barriers to voting for mental health patients is a lack of knowledge about their voting rights. Both patients and healthcare professionals often mistakenly believe that mental health patients, especially those detained under the MHA, are ineligible to vote. This misconception can lead to missed opportunities for these individuals to participate in elections. In 2019, the overall voter turnout was 65%, but the turnout for those detained within mental health units was a shocking 14%. The report goes on to note that:

“…71% didn’t know how to register to vote, 77% didn’t know they could register using the hospital address, and 48% didn’t know they were allowed to vote at all. 50% of those who were unregistered said they would have voted if they had known how.”

Mental health nurses are uniquely positioned to support patients in exercising their right to vote. Given their frequent contact with patients experiencing severe mental illness, nurses can play a pivotal role in educating patients about their voting rights and assisting them in the registration and voting process. Mental health nurses should ensure they have a thorough understanding of voting rights and the specific provisions of the MHA and RPA. They should actively engage in discussions with patients about their rights to vote, provide accessible information, and assist with the registration process. This includes helping patients apply for postal or proxy votes and ensuring they are aware of the requirements for voter ID. More importantly, however, these nurses, who provide invaluable, often thankless, services, need support from higher levels to ensure that this vital right is supported.

Central and North West London have produced a useful information guide to the voting rights of mental health patients, including the following video discussing voting rights with healthcare staff and services users:

Nurses can also advocate for patients by addressing practical barriers to voting. This might involve assisting patients in obtaining the necessary photographic ID or facilitating the application for a voter authority certificate. Additionally, they can work with hospital administration to ensure that information about voting rights is disseminated effectively through multi-disciplinary team meetings, ward meetings, and educational sessions. The Royal College of Nursing notes that:

“Mental health nurses have the most frequent contact with people experiencing severe mental illness. This means as a profession we have a real opportunity to promote patient voting rights. Mental health nurses need to have good knowledge of voting rights and how people with severe mental illness can exercise these.”

Voting is a vital part of social inclusion and democracy, and individuals detained under the Mental Health Act should not be disenfranchised. By understanding the legislation and actively supporting patients, mental health staff can play a crucial role in ensuring that these individuals can exercise their democratic rights. As the next general election fast approaches, it is imperative that mental health services are prepared to support and encourage patient participation in the electoral process.

By fostering an environment where all individuals, regardless of their mental health status, can engage with democracy, we can take significant steps towards reducing social stigma and promoting inclusion for those with severe mental illnesses.

Avaia Williams – Founder

This blog was published on Sunday 30th June 2024