When the rule of law and the conscience of society collide, jury nullification, also known as a perverse verdict, emerges as a dramatic manifestation of this clash. At its core, jury nullification occurs when jurors acquit a defendant, even if they believe he or she is guilty as charged under the black letter of the law, due to their disagreement with the law itself or how it has been applied in a particular case. It’s the jury’s way of saying, “This prosecution should not have happened.”

One of the most famous examples of jury nullification is the case of Clive Ponting. In 1985, Ponting, a senior civil servant in the Ministry of Defence, leaked information to an MP about the sinking of the Argentine warship, the General Belgrano, during the Falklands War, information which contradicted the ‘official story’ at the time. Even though he confessed to the act, which was a clear breach of the Official Secrets Act 1911, the jury acquitted him. They believed his act was in the public interest, they believed his act was morally right and for the benefit of society, showcasing how jury nullification can play out when societal beliefs and moral conscience overpower the law.

Jury nullification is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it can be seen as an essential safety valve, allowing jurors to correct perceived injustices and wrongful applications of law. It’s a system of checks and balances, ensuring that the law remains aligned with prevailing societal values. On the other hand, it might undermine the rule of law and could lead to inconsistency in verdicts. If every jury can interpret the morality of the law differently, doesn’t that destabilise the legal system?

The counter-argument is that jury nullification acts as an essential feedback mechanism. If it happens frequently, it might indicate that a law is out of step with societal values and needs re-evaluation, it might actually encourage Parliament to act or show the CPS that this is not an area where prosecutions should be brought.

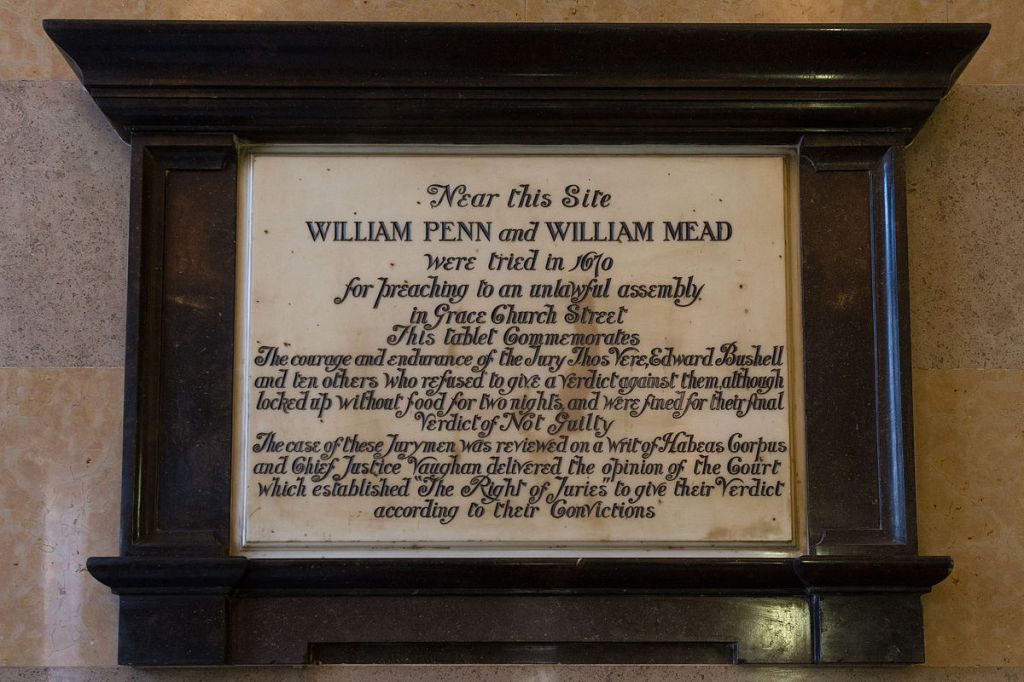

Controlling or regulating jury nullification would be a challenging proposition. A historical cornerstone in this debate is Bushell’s Case of 1670. The case arose from the trial of William Penn, who was accused of preaching a Quaker sermon, which was a crime at that time. The jury refused to convict him, they ruled that he was not guilty of an offence in defiance of the clear law, as a result, they were imprisonment without food. On appeal via writ of Habeus Corpus, it was held that a jury could not be punished for their verdict, that a jury could give a verdict according to their convictions. This landmark case established the fundamental principle that juries must be free and their decisions, even if seen as erroneous by some, should stand.

Introducing regulation would mean treading on this sacred ground. Moreover, it could potentially mean that jury deliberations would have to be entered into evidence. This presents a worrying dimension. The sanctity of the jury room is a tenet of the justice system; breaking it open would not only violate the privacy of the jurors but could also deter honest, open discussion among them. If jurors fear their discussions may be dissected and judged post-trial, they might become less candid, harming the essence of the deliberative process.

If the CPS or any prosecuting entity had the right to appeal a not-guilty verdict, it would erode the defendant’s protection against double jeopardy – being tried twice for the same crime. This would have a myriad consequences, potentially clogging the judicial system and increasing mistrust in its processes, but also bringing the law overall into chaos, resulting in a significantly politicised justice system.

While jury nullification’s spontaneous occurrence is a powerful statement, should we take a step further? What if juries were informed about their right to nullify and were legally permitted to do so when they felt a prosecution was against societal morals and beliefs?

In essence, this would mean transforming a currently covert power of the jury into an overt one. It would be a direct acknowledgment that law, at times, can be unjust or misapplied, and that society, through its jurors, has a right to voice its disagreement. It’s a radical idea but one that has its merits. For one, it makes the legal system more transparent. It recognises the vital role of jurors as representatives of societal conscience. More so, it might also act as a deterrent against questionable prosecutions.

However, such a change would come with its challenges. Legal proceedings could become more unpredictable. It could place immense pressure on jurors, complicating their decision-making process.

A key critique of actively allowing jury nullification is that it could open the floodgates to a chaotic justice system. Jurors, with their diverse backgrounds, might inconsistently apply their personal beliefs, leading to unpredictable outcomes. However, it can be argued that the very diversity of a jury is its strength. Twelve jurors come together to deliberate, reflecting a broad spectrum of society. While one juror might hold extreme views, the collective wisdom of twelve is likely to bring balance. The likelihood of a descent into chaos is very unlikely. Now, that being said, it is important to recognise that jurors can go very rogue, for example, in the 1994 case of Stephen Young, where the jurors admitted using a Ouija Board to inform their verdict.

But, in the age of the internet, TV shows, and widespread media discussions, the concept of jury nullification is better known than ever. This awareness means that jurors are not walking into the courtroom oblivious, nor are jurors delicate beings who cannot be trusted with their own conscience, but rather they have a nuanced understanding of their potential power.

It would be a direct acknowledgment that law, at times, can be unjust or misapplied, and that society, through its jurors, has a right to voice its disagreement. While the proposal carries its challenges, it also offers a pathway to a more transparent legal system, reinforcing the vital role of jurors as representatives of societal conscience.

In a world where societal values are ever-evolving, jury nullification acts as a reminder that laws should be fluid, continually reassessed, and re-aligned with the beliefs of the people they serve. The legacy of Bushell’s case and the tenets of our judicial system provide a bulwark against infringing on this right. Recognising and possibly amplifying the role of jury nullification would empower our legal system to be more just, compassionate, and reflective of the society it serves.

Avaia Williams – Founder

This blog was published on 30 August 2023

One thought on “The Quiet Revolution – Should Jurors Defy The Law?”