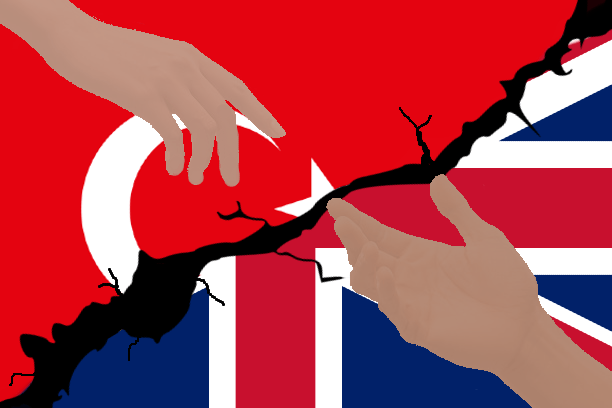

The Istanbul Convention, formally known as the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence, symbolises a ray of hope in the worldwide battle against gender-based violence. Adopted in 2011, this treaty aims to protect women’s rights and eliminate all forms of violence against women, it is also well known as Europe’s first binding instrument on the matter. Its implementation and effectiveness, however, have varied significantly from one nation to another. This article delves into the contrasting approaches of the United Kingdom and Türkiye concerning the Istanbul Convention, shedding light on the challenges and successes these nations have experienced in safeguarding the rights of women and avoiding violation of human rights.

The United Kingdom was quick to embrace the Istanbul Convention and signed it in 2012, formerly ratifying it later on in 2017. The ratification process necessitated amendments to existing domestic laws to ensure alignment with the convention’s provisions. Consequently, the UK incorporated specific measures, such as criminalising forced marriage and female genital mutilation, and enhancing protection orders for victims. This commitment reflects the UK’s dedication to curbing gender-based violence and securing a safer environment for women.

On the other hand, Türkiye was quicker to sign the Istanbul Convention in 2011 but had been yet to ratify it fully, until Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the President of Türkiye, declared the country’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention by presidential decree on 20 March 2021. Despite the initial enthusiasm, Türkiye faced opposition from conservative groups, who argued that certain provisions undermine and make way for the destruction of traditional family values. As a result, the Convention’s ratification process stalled, leaving many of its crucial protections unenforced and highlighted. This lack of formal commitment has implications for the enforcement of anti-violence measures, creating a significant gap in the protection of women’s rights in the country. After being the first country to sign the convention under the same presidency, Türkiye’s desicion to part ways with the convention’s protection, abandoning its effectiveness in furthering human rights and respect all genders equally draw a great deal of attention. The government defended its choice by providing unsubstantiated arguments that the Istanbul Convention was being utilised to “promote homosexuality” and consequently, it was deemed inconsistent and disagreable with the traditional values of the culture.

One of the critical components of effective implementation of the Convention articles is accurate and comprehensive data collection. In this regard, the UK made substantial progress, establishing systems to record and analyse cases of violence against women. These data-driven insights have enabled policymakers to address specific issues and allocate resources more efficiently. Additionally, NGOs and civil society organisations actively collaborated with the UK government to promote a holistic approach to combating gender-based violence.

In contrast, Türkiye faces challenges in collecting reliable data due to underreporting and inadequate coordination among agencies. The lack of a unified system makes it difficult to grasp the full extent of violence against women, hindering the formulation of targeted policies. To address this, Türkiye must prioritise the establishment of a robust data collection mechanism to gain a clearer picture of the issue and implement more effective interventions.

Support and Services for Victims

The UK’s commitment to victim support is observable through the allocation of resources to shelters, helplines, and counseling services. The government has collaborated with NGOs and local authorities to create a network of support systems, ensuring that victims have access to the help they need and when they need it. Moreover, ongoing awareness campaigns seek to destigmatise reporting and encourage victims to seek assistance without fear of retribution and help establish a system of reflective thinking on the matter.

In Türkiye, although some support services exist, they often face challenges in funding and capacity. Cultural barriers and societal impediments discourage victims from coming forward, leaving them vulnerable and isolated. To improve the situation, Türkiye must prioritise the funding of support services and work tirelessly to shift societal attitudes, making it safer for victims to seek the help and support which they require and deserve.

The Istanbul Convention stands as a transformative force in the global struggle for women’s rights. While the United Kingdom has made significant strides in implementing the Convention’s provisions, Türkiye faces challenges in fully realising its potential. However, despite the potential dangers of police restrictions and the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic in the country, crowds of people have taken to the streets to protest. The resistance extended beyond just demonstrations, as individuals and groups resorted to strategic litigation in a way never before seen in Türkiye’s political history. By learning from each other’s experiences and building on successful strategies, both the UK and Türkiye can work together to create safer, more equitable societies for women. The path towards comprehensive gender equality is a long one, but the Istanbul Convention offers a roadmap to it that, if followed diligently, can lead to a brighter future for all genders worldwide.

Articles of The Istanbul Convention

The Istanbul Convention consists of 81 articles that advocate an extensive range of tangible actions aimed at preventing violence against women, protecting victims, and bringing perpetrators to justice.

- Purposes (Article 1): This article includes safeguarding women from all types of violence, promoting gender equality, establishing comprehensive frameworks for victim protection, fostering international cooperation to combat violence against women and domestic violence, and supporting collaboration among organisations and law enforcement agencies for a holistic approach to ending such violence.

- Definitions (Article 3): This article provides clear definitions of various terms used throughout the Convention, ensuring a common understanding of terms like “violence against women,” “domestic violence,” and “gender.”

- Scope (Article 4): The Convention’s scope extends to all forms of violence against women, including physical, sexual, psychological, and economic violence, as well as stalking, forced marriage, and female genital mutilation.

- General Obligations (Article 5): Parties to the Convention are required to take comprehensive and coordinated measures to prevent violence against women, protect victims, and prosecute perpetrators.

- Non-Discrimination (Article 6): Parties must take measures to ensure that the Convention’s implementation does not discriminate against women on any grounds, such as race, ethnicity, religion, disability, or sexual orientation.

- Preventive Measures (Article 7): This article outlines measures for promoting gender equality, education and awareness-raising initiatives, and addressing the root causes of violence against women.

- Protection and Support (Article 8): Parties are obligated to provide appropriate support and protection services to victims, including access to shelters, helplines, counseling, and legal assistance.

- Law Enforcement and Prosecution (Article 9): This article focuses on ensuring effective law enforcement, prosecution, and judicial cooperation to hold perpetrators accountable.

- Integrated Policies (Article 10): Parties are encouraged to develop and implement comprehensive, multi-sectoral policies and action plans to address violence against women.

- Monitoring Mechanism (Article 11): The Convention establishes a Group of Experts on Action against Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (GREVIO) to monitor its implementation and provide recommendations to parties.

- Specialised Bodies (Article 12): Parties are encouraged to establish or designate specialised bodies to address violence against women effectively.

- National Helplines (Article 13): Parties should consider establishing toll-free national helplines to provide information, support, and assistance to victims.

- Data Collection (Article 14): Parties are required to collect and analyse relevant data on violence against women to inform policymaking and assess the impact of measures taken.

- Education (Article 15): This article focuses on integrating measures to prevent violence against women into educational programs and training for professionals working with victims.

Other articles that the convention includes, but are not limited to, are: Awareness-Raising (Article 16), Duty of the Parties (Article 18), Custody, Visitation Rights, and Safety (Article 31), Measures Relating to Persons at Risk (Article 63), and Territorial Application (Article 77). The enforcement of the Convention is imperative to effectively tackle and eradicate violence perpetrated against women and domestic violence, thereby fostering a safer and more egalitarian society for all its members.

Melis Erdogan – Writer

This blog was published on 31 July 2023